The first automatic pistol designs were blow back operated. This design has a frame-mounted, immoveable barrel which demands a heavy slide. This provides sufficient inertia to hold the slide in place long enough for the bullet to leave the barrel and gas pressures to reduce to safe levels. If the slide isn’t heavy enough, it will come out of battery, moving to the rear before the bullet has left the barrel!

John Browning’s first automatic pistol, the FN Model 1910 in .38 AUTO had a gas block and piston, just as the AR-15 does. The gas went out a port at the end of the barrel and was sent to the breach, pushing it back, to extract and eject the case. Think lots of levers and gears. It wasn’t pretty, but it worked.

So a blow back pistol action uses the excess gas from the cartridge to push the slide to the rear, extracting and ejecting the case. It’s the recoil spring which, now compressed, brings the slide forward, cocking the hammer, stripping a new cartridge from the magazine and chambering it.

James Bond’s iconic Walther PPK is a blow back pistol. If you remove the slide from the pistol, you can see that the barrel is part of the frame and cannot be removed.

So how does a blow back pistol differ from today’s common recoil operated pistols? Well, first of all, the proper term for today’s semi-automatic pistols is “short recoil” because our hero, John Moses Browning, put most of the works “in front” of the breach, in an extension of the breach which we now call “the slide.” Before Browning, there was no slide wrapped around the barrel. The recoil is short because the slide only needs to go back the length of the cartridge, so it can be extracted and ejected from the gun.

The short-recoil operated pistols have a removable barrel which drops out of the way a very short distance after the slide begins to move rearward. In Browning’s original design, the barrel actually dropped, parallel to the slide, out of the way, using linkages with pins on both ends. That didn’t work too well, so he switched to a single linkage at the rear of the barrel, tipping it down, allowing the slide to continue to the rear while the barrel stayed put.

This is what you find in the Colt 1911 – a tipping barrel articulating on a linkage and pin. We no longer need a really heavy slide to keep the gun in battery for a time. Now the barrel and slide are locked together with lugs (called “in battery”) moving rearward together until the bullet has left and the gasses have dissipated sufficiently. Then the barrel drops into a recess, caught by the barrel lugs against the frame, while the slide continues rearward. Brilliant!

This genius invention remained the primary means of operating a short-recoil, hammer-fired pistol for about 75 years. In fact, I would argue that today’s striker-fired pistols operate in the same way Browning introduced, but the slide doesn’t cock the hammer any longer, it pre-tensions the striker.

So how does the blowback pistol differ from the delayed blowback pistol?

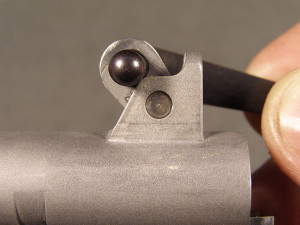

I just did a review of the Walther CCP (concealed carry pistol.) It’s a delayed blowback pistol. The blowback operation depends on the weight of the slide to ensure the gun stays in battery until the bullet has left the barrel. The delayed blowback operation actually retards the rearward movement of the slide with gas pressure and a piston. Here’s the inside of the slide on the new Walther CCP.

Notice the piston attached to the front of the slide? Hot gas behind the speeding bullet is siphoned out of the barrel, through a small hole in the barrel, and fills a gas chamber below.

The gas pushes against the piston, keeping the gun in battery until the bullet leaves the barrel. The weight of the slide is no longer a factor. The recoil spring we all struggle with to rack the slide need not be so robust to counteract the force of the slide being thrown rearward. This design results in softer recoil and an easier recoil spring to compress.